by Joseph Hooper

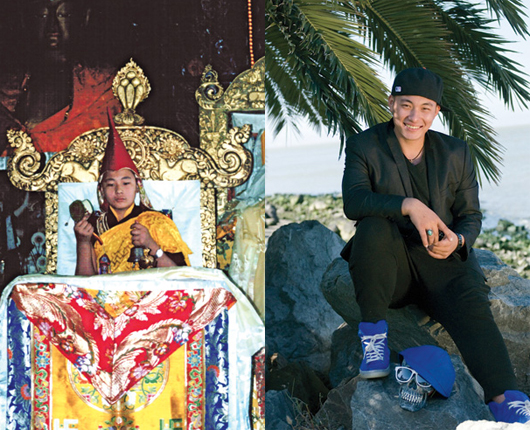

KALU RINPOCHE: THE PRODIGAL SON

One of Tibetan Buddhism’s brightest stars and greatest hopes is 22-year-old Kalu Rinpoche, the head of a global Tibetan Buddhist enterprise of 44 monasteries and teaching centers, including 16 in the United States, that engage thousands of students and disciples. Many of those followers are inherited, the result of his being recognized at the age of 2 as the incarnation of Kalu Rinpoche, who died in 1989 and was one of the most influential lamas in the West aside from the Dalai Lama.

Young Kalu travels the world, mostly alone, visiting his meditation centers and monasteries or just amusing himself in countries with relaxed visa requirements. His real monastery is online—Kalu calls himself “the first Facebook rinpoche,” managing a network of personal and public pages with thousands of friends and “likes.” Most are generational peers who have discovered that it’s pretty cool to get a personal message from a bona fide lama.

Kalu is a lithe, smoothly good-looking young man with a fast-receding hairline, long sideburns, and a white roadster cap—something like a hipster version of a golf caddy. He exudes a pop-star vibe, which is appropriate given his lifestyle. The first thing we establish over the course of a series of Skype sessions is that he’s at a hotel in Hong Kong and not, as his Facebook posts lead his “friends” to believe, in India. He likes to play with identity as well. This spring, his personal Facebook page assumed the names of, variously, Kalu Andre (he loves Paris and left there only because his visa ran out), Kalu Skrilles (he’s a fan of Skrillex), and George Kalooni (just because).

Born into a well-connected Tibetan family, living in both India and Bhutan, Kalu absorbed Western culture in dribs and drabs as a boy in his home monastery near Darjeeling, India. “We shared—200 people—one small TV,” he says. “We watched Van Damme and Arnold Schwarzenegger.” He picked up English slang from American films and music (the Backstreet Boys were big). “Since I was a kid,” he says, “I don’t think, ‘This is the West.’ I think, ‘This is real. This is what I want.'” When he left monastery life two years ago to begin his career as a global emissary, he consumed a decade’s worth of popular culture in one giant gulp. Favorites include, in music, Foster the People and deadmau5; on TV, Gossip Girl (“full of drama”); in film, The Hangover. “I’m a fan of the first Hangover—the second was not as good,” he says. “I like Bradley Cooper. He’s very attractive-looking.”

For all the pleasures of a social-networked life, Kalu is lonely, a Buddhist Little Prince adrift on a cyber-asteroid. “Actually, I never had a true friend,” he says. “Never felt that he is or she is my best friend. A relationship is a different thing.” About a year ago, he came close to marrying a well-to-do Tibetan girl, and he’s currently “on a break” from an Argentine girlfriend. In a later conversation, though, he apologizes for the no-friend remark—”I was a little tipsy and depressed”—and then repeats it almost verbatim but says of the loneliness, “I can handle it.”

To appreciate Kalu is to see him as two things simultaneously. He’s a troubled kid and a spiritual adept whose gifts were refined during the traditional three-year retreat he undertook in his teens—the last year of which was spent in near-constant meditation and yoga practice. Kalu recognizes that it’s time to exert more control over a life that has been marked by emotional chaos. He has shelved a plan to study comparative religion at an American university in order to maintain some measure of authority over his organization. Yet the senior lamas in Kalu’s order have had to step in to fill the power vacuum created by his erratic lifestyle and propensity to say whatever is on his mind.

Last September, after a teaching session in Vancouver, someone in the audience asked Kalu about sexual abuse in the monasteries. He replied that he was sensitive to it because he had been molested. That seemed to break through the wall that had sealed his private traumas off from his smiling public persona, which had the aura of an updated, hipper Dalai Lama. Two months later, Kalu returned to his temporary home base in Paris and shot a video that he posted on Facebook. Titled “Confessions of Kalu Rinpoche,” the video has since gone modestly viral on YouTube and turned him into an outcast in the traditional Tibetan Buddhist world and a hero of conscience to some in the West.

In the video, Kalu sits in a hooded parka and tells the camera that as a young teen he was “sexually abused by elder monks,” and when he was 18 his tutor in the monastery threatened him at knifepoint. “And it’s all about money, power, controlling. . . . And then I became a drug addict because of all this misunderstanding and I went crazy.” Near the end of the video, he says in an almost suicidal-sounding whisper: “Anyways, I love you. Please take care, and I am happy with my life.”

For those who know only the gauzy Hollywood imagery of Little Buddha and Kundun and the beatific smile of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, it’s almost incomprehensible that Tibetan Buddhism would have its own Catholic Church–style problem. But Kalu says that when he was in his early teens, he was sexually abused by a gang of older monks who would visit his room each week. When I bring up the concept of “inappropriate touching,” he laughs edgily. This was hard-core sex, he says, including penetration. “Most of the time, they just came alone,” he says. “They just banged the door harder, and I had to open. I knew what was going to happen, and after that you become more used to it.” It wasn’t until Kalu returned to the monastery after his three-year retreat that he realized how wrong this practice was. By then the cycle had begun again on a younger generation of victims, he says. Kalu’s claims of sexual abuse mirror those of Lodoe Senge, an ex-monk and 23-year-old tulku who now lives in Queens, New York. “When I saw the video,” Senge says of Kalu’s confessions, “I thought, ‘Shit, this guy has the balls to talk about it when I didn’t even have the courage to tell my girlfriend.'” Senge was abused, he says, as a 5-year-old by his own tutor, a man in his late twenties, at a monastery in India.

Kalu’s run-in with his monastic tutor was anything but typical. According to Kalu, after returning from his retreat, he and the tutor were arguing about Kalu’s decision to replace the tutor. The older monk left in a rage and returned with a foot-long knife. Kalu barricaded himself in his new tutor’s room, but, he says, the enraged monk broke down the door, screaming, “I don’t give a shit about you, your reincarnation. I can kill you right now and we can recognize another boy, another Kalu Rinpoche!” Kalu took refuge in the bathroom, but the tutor broke that door, too. Kalu recalls, “You think, ‘Okay, this is the end, this is it.'” Fortunately, other monks heard the commotion and rushed to restrain the tutor. In the aftermath of the attack, Kalu says, his mother and several of his sisters (Kalu’s father had died when he was a boy) sided with the tutor, making him so distraught that he fled the monastery and embarked on a six-month drug-and-alcohol-fueled bender in Bangkok, a more extreme Tibetan version of the Amish rumspringa. Afterward, an elder guru persuaded Kalu to continue as a lama away from the monastery and without the robes of a celibate monk, a not-uncommon arrangement. Kalu never said a word to the guru about what had precipitated his flight, a level of decorum that may seem bizarre by Western standards—but Kalu says a form of omertà pervades Tibetan Buddhism.

The Western Buddhist media have barely touched the Kalu story, which may represent its own form of decorum: not wishing to demoralize American converts or roil the waters among powerful Tibetan Buddhists. But some younger, Western Buddhists, like Ashoka and his half-brother Gesar Mukpo, the director of the 2009 documentary Tulku, say they find Kalu’s raw honesty inspiring. Ruben Derksen, a 26-year-old Dutch tulku who appears in Gesar’s film, says that it was about time that Tibetan Buddhist institutions were “demystified and the shroud was removed.” Derksen, who as a child spent three years in a monastery in India, wishes to draw attention to the physical beatings that are a regular practice there. “I met Richard Gere and Steven Seagal, and they didn’t see any of this,” he says. “When celebrities or outsiders are around, you don’t beat the kids.”

Kalu’s revelations have quietly rocked the Tibetan Buddhist establishment, and even some of its most distinguished figures have been taken aback. Robert Thurman, the Columbia University professor and the Dalai Lama’s American confidant (and yes, Uma’s father), says of Kalu’s video, “I thought it was one of the most real things I’ve seen.” About the knife-wielding incident, which some might find hard to credit, Thurman wrote in a subsequent e-mail, “Sadly, it all does seem credible to me. . . . The whole thing just reeks to high heaven.” Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, the lama who directed The Cup, the one relatively unsentimental feature film about Tibetan children raised as monks, is concerned about sexual abuse at monasteries. “I think this is something we should look at,” he says. “It’s very important that people don’t forget: Buddhism and Buddhist are two different entities. Buddhism is perfect.” Buddhists, he suggests, are not.

In Kalu, there is a reformer struggling to emerge from the self-pitying victim. He plans to open his own school in Bhutan and to forbid his monasteries from accepting children. He rails about the human costs of the monastery system that consumes thousands of kids, both workaday monks and revered tulkus, providing them with no practical education or fallback plan, all to produce a handful of commercially successful spiritual masters. “The tulku system is more like robots,” he says. “You build 100 robots, and maybe 20 percent will be successful and 80 percent will go in the trash.”

Joseph Hooper

Souce: http://www.zbigniew-modrzejewski.webs.com/teksty/kalu.htm

One Response to “Leaving Om: Buddhism’s Lost Lamas ”